This post was most recently updated on January 11th, 2017

Walking into camp. We have warm boots. Many of the refugees are wearing sandals and lack warm clothing.

Arriving on Friday morning in the camp was strange, yet familiar. This time I was with Linda, an experienced homestart manager who has previously done 5 days in the camp, and Katie, a doula for whom this was her first visit.

We had a car load of donations to take to the women’s centre – buckets for sterilising cups and dummies, infant feeding cups, nappies, wipes, baby clothes, fabric to make the centre look welcoming and warm, toiletries, warm pygamas for the children. There was no way we could carry all that from the gate to the centre, so we embarked on our first challenge; charming the guards into letting us drive into camp. After much waiting in the cold, we are granted 5 mins to drive in, unload, and drive out again.

After stowing away our donations and talking to the women’s centre volunteers about what we had brought we began to plan our day. Linda wanted to go over to the children’s centre to make herself useful there. Katie and I were to meet with the GSF Midwives to talk about infant feeding practices in the camp.

We sat around the wood burner, a few children, a couple of mothers and us, chatting and getting a feel for the atmosphere in camp. It was quiet. Yet again there was no electricity in the building and things seemed more down at heel, even than since my last visit. The centre was starker, less friendly-seeming, and things felt a little more strained; the volunteers a little more hassled.

It quickly became clear that one reason for this was the fact that there are now over 100 homeless people living in camp. This is because if a family leave camp to try to reach the UK and are away for more than a day or two, the authorities tear down their shelter. If they fail in their efforts, they may spend many hours walking back to camp, only to find they no longer have a place to sleep or keep warm and relatively dry. Many of these homeless men were breaking into the Woman’s Centre every night, burning anything that wasn’t nailed down in order to stay warm. As the weather gets colder and everyone feels a bit more desperate and depressed, alcohol starts creeping into the equation. Alcohol + machismo + organised crime…it’s a volotile combination.

So the safety of the centre has been compromised. The haven for mothers and babies is no longer as it was. In desperation the volunteers have decided to convert one of the lorry containers (that forms one side of the centre) into a safe room for the mothers. A place to feed their babies, have pamper evenings, learn languages, and provide each other with social support. The walls of the container were insulated, carpet put on the floor and rugs, pretty fabric to hang on the walls and cushions were being collected. It warmed my heart to see what could be achieved in the midst of everything and such a transformation from clothing store to chill-out space in such a short time. We knew we had to buy some rugs and cushions to help finish the space.

It was time to go to our meeting with the midwives. It was so good to have Katie with me, to take the minutes and bouy me up with moral support. The midwives are lovely – young and friendly and clearly passionate, but obviously completely oblivious to the dangers of powdered formula in emergency conditions. They listened intently and we reached some positive compromises and the meeting concluded with kisses – a social convention that I love as it really does oil the wheels of friendship! We are all agreed that we need to work towards a powdered formula-free camp and for babies who need formula milk to be cup-fed with ready-made liquid formula to minimise the risk of bacterial contamination.

There is still a problem with donations of powdered formula coming into camp. If you are reading this, and don’t fully understand why this can’t continue, please read this information about feeding in emergency situations and if you come across well meaning people organising donations of powdered formula or anything other than stage one ready made up infant milk please share best practice with them and help educate the public. Babies fed by bottle on powdered formula in unsanitary conditions are many, many more times more likely to die.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Off we go to the supermarket! As usual, the juxtaposition of extreme privation and middle class consumerism is very jarring. We fill our trolleys. The most affecting request is adult incontinence pants for the women. There are no lights in the toilet blocks and no lights in camp. The women are frightened to go to the loo or traipse their kids across the field in the middle of the night in the cold and pitch dark. The toilets are wet and dirty and even in the day time, once you close a cubicle door, pitch dark. So the women and children wear nappies at night.

We grab some lunch while in the supermarket complex and head back to camp. The nice guard from earlier lets us drive in again, right up to the Women’s Centre so we can unload. We bring back lots more full fat UHT milk for the children, blankets, rugs and cushions, a couple of new baby buggies…it feels good to spend the money so generously donated by my friends and family.

We wander around camp. We have much needed woollen gloves and hand warmers to give away. We meet a mother with a very new baby – only 4 weeks old. We arrange to see her the next day to talk about how the feeding is going. We also arrange to do a training session for some new Woman’s Centre volunteers the next morning.

Linda goes back to see some friends – a large family of 8 including 3 children under 5, all sleeping in a shelter about the size of your garden shed.

It is getting colder and greyer. People’s jaws are set a little more tighter, shoulders a little more hunched. It’s time for us to go for the evening and make plans for the morrow. We retire to our hotel, feeling guilty we can leave for a hot shower and a good meal. We fall into our beds exhausted and sleep fitfully.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

We are up early, off again to the supermarket with another shopping list. My phone is low on charge so I leave it switched off in the car. Later I was to see the missed calls and texts from Sasha, the woman’s centre volunteer. In a way, I’m grateful for the hour or two we had not knowing.

At the gate, it was a security guard who broke the news. The young friendly chap of yesterday was not here and this guy wasn’t bending any rules for us at all. “No car, no way”. So we gathered our purchases and staggered into camp, past the midwives clinic, past the community kitchen and all the way up the path to the woman’s centre. Only to see that the guard was right – there had indeed been a fire in the night.

A devastating fire. The woman’s centre was gone. Completely gone. The volunteers and some of the refugee women and children stood around in silence. No one knew what to say. We hugged. We cried. We began to ask questions. No one seemed to know what had happened.

Caroline, Women’s Centre volunteer looks at the devastation

What was clear was that the lorry container that was being converted into a safe, quiet room for the mothers had been broken into and gutted by fire, along with the main space. A deliberate act. Whether it was pre-meditated or just the result of desperation and alcohol, we don’t know.

What we do know is that there are some very bad men. A criminal element intent on making money from these people. Those still carrying their life savings with them will pay for passage. £3000 is the going rate to be trafficked to the uk.

There is nothing to do but ‘chin up, shoulders back’ and get on with the day. The mums still needed stuff. There was no water, no toilet paper and the kids needed cheering up. So during the afternoon we went shopping again and organised pizza for all the kids in the children’s centre.

Linda outside the children’s centre

And we needed to check on some mums with little babies. We met a mum with a small baby – around 3ms old. She looked South East Asian. She told us she was breastfeeding and we congratulated her and admired her gorgeous baby. At that moment, two French women arrived at her door, offering her baby milk. In a trolley behind them were dozens of tins of powdered formula. We did some hasty explaining of why giving out powdered milk is not a good idea and explained what to do instead. We have no idea who these women were. There is clearly a need for stricter controls on the donations that are brought into camp.

But if even professional midwives need persuading that it is not appropriate to accept inappropriate donations, we have quite a way to go before we can make sure the camp is a safe place for babies.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

We go off to visit the mother we’d met the day before, with the month old baby. Like all the other Iraqi Kurd mothers I’ve met, she ushers us into her shelter with an enormous smile and looks so proud to unwrap her baby from his many layers and show him off. He is gorgeous; big eyes and a shock of dark hair and a good weight. Before I can even think about putting on my breastfeeding counsellor hat and asking her about feeding, we burst into tears. The desperation in her voice is obvious. In very broken English she tells us about her big boy. He is 18, the product of a previous relationship. He has managed to get to England, but she hasn’t heard from him for months. We can see her pain. I think of my 16 year old son, and how I’d feel if he disappeared without trace. I didn’t know my heart could break more than it already has.

She told us about her journey here. Running from terror, they managed to get to Turkey and paid traffickers $12,000 for passage by sea to Italy. She was 38 weeks pregnant when she embarked on the journey. The boat was small, with no shelter from the elements and no toilets. 250 frightened refugees endured 5 days on that boat.

Her baby was born in Italy. It was a fast labour. She says the staff were kind and everyone fell in love with her beautiful baby. I don’t know how she got to France in the 4 short weeks since the birth, still bleeding, still establishing lactation, still exhausted from pregnancy, birth and an epic journey.

The mood is lifted when we talk about feeding. She is exclusively breastfeeding and is proud of her milk supply, which is abundant, and her baby’s weight gain. I gave her some information about feeding in her own language and warned her about the formula donations in camp, reminding her that how she feeds her baby is her choice and that how she is caring for her baby now is safe, healthy and protects him from infection.

We gave her some nappies and wipes and a snow suit and hat for the baby, a light for her shelter and a hot water bottle – changing the baby’s nappy at night is traumatic because it is so cold, the baby cries and cries.

We said our goodbyes and went to find the woman’s centre volunteers to say goodbye to them. They were pushing a shopping trolley around camp, giving out nappies and other essentials supplies. They look shellshocked, dead-eyed, heartbroken.

No one knows what will happen next. The deterioration of the camp will inevitably lead to even more tensions and deprivation and that leads to bad feeling and violence and a way in for organised crime, drugs and alcohol. What was set up as a safe place for families with nothing is no longer meeting international humanitarian standards.

One of those standards must be a centre for women; a safe place to get emotional support, help and information around feeding babies and young children, health promotion advice, comfort and a tiny little bit of normality. It is imperative that the Grande Synthe town hall give permission for a new structure to be built as soon as possible.

Honestly, what hope can we give these people when they are living in such a way? No wonder they are desperate to leave the camp and come to the land from which so many of the kind volunteers come. The traffickers tell them everything is free in England and the streets are paved with gold. Of course they are following the rainbow. Misguided, maybe, but understandable, given the traumas they have been through and the conditions they are currently enduring.

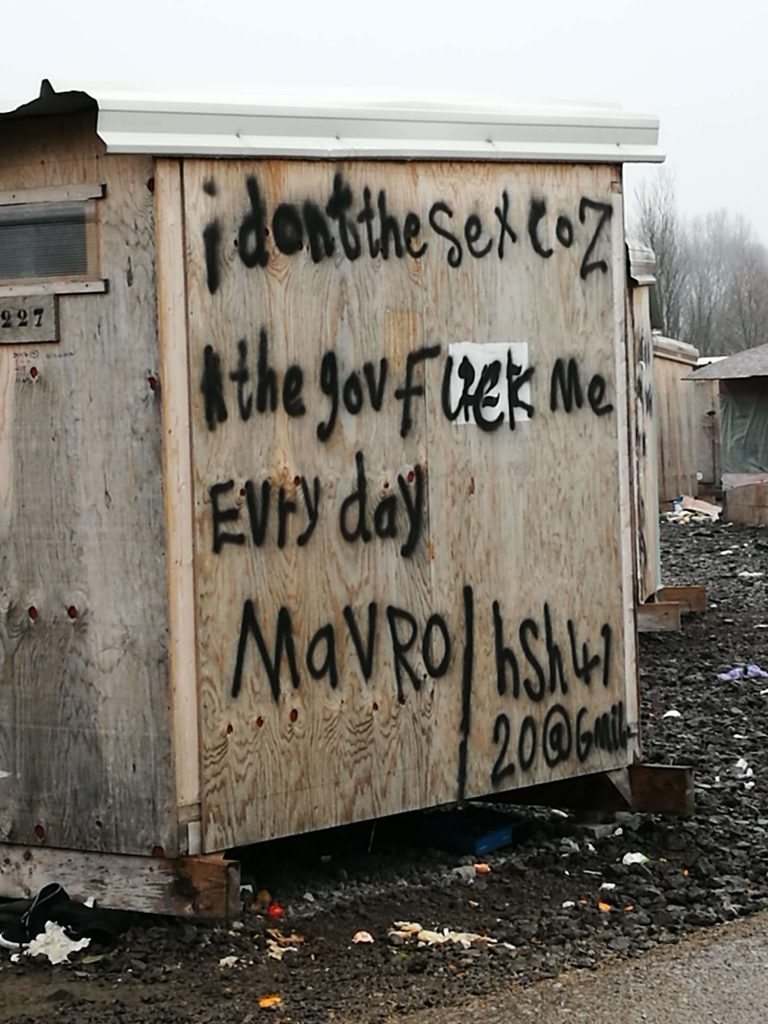

As this refugee says so eloquently, what else do you need when the authorities are are effectively leaving you high and dry?

I don’t need sex coz the government fuck me every day

How can you help? Donate to the Infant Feeding Team

If you are a Peer Support, Breastfeeding Counsellor or IBCLC we need volunteers to make regular visits and a longer term volunteer to be an infant feeding lead for the camp. Get in touch if you’d like to know more ([email protected])

Read more about infant feeding in emergencies here

I worry that simply rebuilding the women’s centre, without addressing the reasons for the destruction, will simply mean that there is another fire.

This is a complex problem. The aim for everyone is surely to stem the tide of refugees to the camp, and to get the people currently there, out of the camp, and into safe lodgings.

Is improving conditions in the camp the best way to do this?

Whatever the long term solutions, clearly in the short term people need adequate shelter and a safe place to breastfeed their babies. And I’m so pleased you’re involved, helping. But it’s going to need phenomenal resources to resolve this crisis.

It totally is a complex problem. I don’t pretend to have a political overview – it is up to people much more powerful than me to sort this problem once and for all. If the French government really did care, they could properly house all them tomorrow, but they clearly do not intend to extend that kind of kindness to their visitors. The people Calais were dumped in Paris without any help and thus there are hundreds sleeping on the streets.

In the meantime, the camp HAS to adhere to minimum international humanitarian standards. I cannot, and never could, countenence making conditions even more difficult, just to try to discourage people from coming. A) that wouldn’t work because the traffickers sell people an image of Europe that is not true and B) conditions in their home countries are untenable, so migration is utterly predictable until those countries are safe to live in.

All I care about in the short term. These people need help, now. The fact they are being treated so abysmally is a shame on us Europeans.

Anyone who has a modicum of imagination can picture what it might be like to be living in a garden shed in this weather. This is only going to get worse as the weather gets colder.